In the US, retail health clinics are now a permanent part of the health care landscape with the potential to become a much more powerful enabler of a “culture of health,” according to a recent report by Manatt Health, the health care division of Manatt, Phelps & Phillips.

This perspective will be of interest to Australian pharmacists who are just beginning to “test the water” in respect of clinical services and clinic development.

It comes at a time when Australian pharmacy is being subjected to extreme financial pressure brought on by a federal government showing scant sympathy for pharmacy as a small business, as negotiations for the 6CPA get under way.

Government funding is likely to be restricted for Australian pharmacy clinics, so much of the pioneering and establishment costs will need to be met privately.

The US report, titled “Building a Culture of Health: The Value Proposition of Retail Clinics,” examines the potential value proposition of retail clinics. It was guided by an advisory committee, and informed by published research and interviews with 20 retail clinic experts and stakeholders and thus is a useful guide for Australian pharmacists.

According to the paper, prepared for the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the number of retail clinic sites increased almost 900% between 2006 and 2014, from 200 to 1,800, and the number of visits increased seven-fold from approximately 1.5 million to 10.5 million in 2012, representing upwards of 2% of primary care encounters in the United States. Australian pharmacy has had a long involvement in the primary health care space and over the last decade has lost ground to other health care practitioners.

Thus, the upbeat nature of this report provides a glimmer of hope in a landscape where PBS income is rapidly evaporating coupled with a retail market that is intensely competitive and too costly to compete against.

Health clinics delivering primary health care appear to be the promising “hook” for Australian pharmacists to invest their skill and capital in.

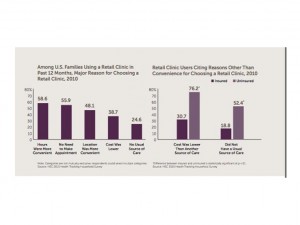

“Demand for convenient access to care for low-acuity, time-sensitive conditions or routine preventive services has been fueling clinic growth. The vast majority of clinic users reported that the primary purpose of their most recent clinic visit was the diagnosis and treatment of a new illness or symptom, followed by vaccinations and prescription renewals,” the report stated.

The report also noted that telehealth has the potential to reduce cost and improve both access to care for rural and under-served communities and support treatment of patients with acute and chronic conditions at retail clinics and beyond as live telehealth consults can be used to extend the scope of consultative, diagnosis and treatment service options.

All the above looks promising for the Australian health landscape found in regional, rural and remote Australia.

Even though US clinics have had a head-stat over Australian counterparts, researchers noted that there are several hurdles to overcome for US clinics e.g. scope-of-practice rules that constrain services in many states and a lack of government reimbursement.

Researchers noted, for example, that Medicare only covers reimbursement for telehealth in limited settings, and never in retail clinics.

These are problems that also exist in Australia, so it would seem that it will be a “hard slog” to get Australian clinics to a desirable level even though they hold the promise of providing economical and convenient solutions to Australia’s health care system.

No doubt the people involved in developing political campaigns for the Australian Medical Association (AMA) have pharmacy clinics in mind when they run negative advertising and political strategies continually against pharmacies, almost it seems on a weekly basis.

Other points noted in the report are summarised below.

They bear an amazing resemblance to the Australian experience, envisaged and actual.

“Retail clinics are businesses operating on thin margins, and like any other low-margin business, they must pay close attention to reimbursement for the services they provide and the direct and indirect revenue they generate for the retailer.

And while retailers, health systems and payers recognize the impact of social determinants on health outcomes, most have not yet embraced initiatives that help improve population access to in-store offerings and public programs that address their non-clinical needs.

These are weighty challenges; if retail clinics overcome them, they have the potential to become a much more powerful enabler of a Culture of Health,” the report stated.

Australian pharmacy clinics have had a slow start because the pharmacy trade union, the Pharmacy Guild of Australia (PGA), has tried to anchor all available income through clinical services as being “owned” by a pharmacy.

Although there is still a way to go, realisation that the clinical business is inherent within each clinical pharmacist is slowly evolving and there is a move towards alliance partnerships.

As an interim measure, those services that have a design component that can be “commoditised” are being developed and pursued for government funding.

Unless Australian pharmacy culture is universally aligned, we will continue to see slow and hesitant growth until market confidence builds and investment increases.

At that point we will probably see a rapid growth similar to the US experience, and the new paradigm pharmacy will be recognisable and well under way.