Pharmacy Practice is undergoing a review process in Australia because the primary source of income (the PBS) for community pharmacy has reached the end of its life-cycle.

The future of the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme indeed looks bleak so re-modelling of dispensing services is unavoidable.

Many aspects of Australian pharmacy practice have been one of the best kept secrets – ever!

The reason?

Pharmacists come under attack from the medical profession if they move into aspects of patient care that involve diagnosis, prescribing and referral to areas of skilled care rather than to doctors.

In my early apprentice days I was taught to not mention the words diagnosis or prescribing in the context of any patient clinical service.

I could use words such as “recommendation”, “advice”, “counselling”, and I could refer patients informally (not documented) to health practitioners and GP’s.

Medical pressure ensured that the cost of providing a clinical service had to be recovered in the form of a product sale, particularly a product specially compounded by the pharmacist, which meant that the patient usually (and quite happily) returned to their pharmacist for a repeat of the medicine or any expansion of advice.

Global pharmaceutical manufacturers have always viewed compounding pharmacists as a block to their marketing channel for branded drugs, delivered by doctor prescriptions.

Hence their financial support for doctors to encourage brand prescribing.

Thus the culture that I worked with in my apprenticeship days has carried forward to the present day, except that pharmacists today are identifying their practices openly and seeking recognition and payment for these services separate to a product sale.

The doctors, principally through the lens of the AMA and the RACGP, see all pharmacy moves as a “turf war” and oppose virtually anything.

The only difference today is the fact that doctors have lost their punitive power to channel prescriptions, an action that could destroy an offending pharmacy practice in the past.

Prescriptions were once valuable, but are now virtually of no value, so the playing field is more even and pharmacists can now tell the medical world to politely “get stuffed!”

i2P encourages all Australian pharmacists to practice to the limit of their licence and to do it as quickly as possible before the medical and global drug company lobbies can mobilise against you.

It was not until 1993 that pharmacy practice guidelines were formally established through the International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP) when they adopted the guidelines for Good Pharmaceutical Practice .

These guidelines were developed as a reference to be used by national pharmaceutical organisations, governments, and international pharmaceutical organisations to set up nationally accepted standards of Good Pharmacy Practice.

A revised version of this document was endorsed by WHO in 1997 and subsequently approved by the FIP Council in 1997.

In 2011, FIP and WHO adopted an updated version of Good Pharmacy Practice entitled “Joint FIP/WHO guidelines on good pharmacy practice: standards for quality of pharmacy services”.

In this document, the aim of pharmacy practice is defined as to “contribute to health improvement and to help patients with health problems to make the best use of their medicines.”

GPP is defined as “the practice of pharmacy that responds to the needs of the people who use the pharmacists’ services to provide optimal, evidence-based care.

To support this practice it is essential that there be an established national framework of quality standards and guidelines.”

Australian pharmacists need to be aware that external lobbyists, generally, with drug manufacturer backing, try to manipulate these guidelines and standards.

The recent attack on homeopaths and their swift denunciation in the APLF guidelines is an example of a guideline that is really an unethical attack on homeopaths – something that Australian pharmacists should not be a part of.

The more disturbing aspect underlying that attack was manipulation by the same lobby group of our once prestigious NHMRC , now untrusted because it is no longer neutral.

The WHO/FIP 2011 GPP document underlines the requirements of Good Pharmacy Practice and how to set standards required for GPP, (which also imply a quality management framework and a strategic plan for developing services).

GPP are organised around 4 major roles for pharmacists:

Role 1: Prepare, obtain, store, secure, distribute, administer, dispense and dispose of medical products

Role 2: Provide effective medication therapy management

Role 3: Maintain and improve professional performance

Role 4: Contribute to improve effectiveness of the health-care system and public health

Each function is structured in several roles, and for each role, a list of minimum national standards to be established have been set.

* WHO/FIP… GPP should serve as a guidance document for the development of specific standards of GPP at national levels by national pharmacists associations and other related stakeholders.

* When establishing minimum standards on GPP, it is important to define the roles played by pharmacists, as expected by patients and society.

This is an area relevant to the “Advanced Practitioner” documentation currently being developed here in Australia.

The people involved here should be very careful to consult a wide range of “grass roots” consumers and practising clinical pharmacists before introducing any guidelines that may end up inhibiting progression of pharmacist aspirations.

* Relevant functions for which pharmacists have direct responsibility and accountability need to be determined within each role in a very broad context.

* Minimum national standards should then be established, based upon the need to demonstrate competency in a set of activities supporting each function and role.

In addition to the FIP involvement in Good Pharmacy Practice through these Guidelines, FIP together with WHO has published a joint handbook entitled “Developing pharmacy practice – A focus on patient care”.

This handbook sets out a the new paradigm for pharmacy practice.

Its aim is to guide pharmacy educators in pharmacy practice, to educate pharmacy students and to guide pharmacists in practice to update their skills.

The handbook, which brings together practical tools and knowledge, has been written in response to a need to define, develop and generate global understanding of pharmaceutical care at all levels.

It is also at this level that Australian pharmacists need to be able to scrutinise and to oppose any guideline adverse to clinical pharmacy practice expansion.

And also for this reason, Australian pharmacists should expand their clinical service activity across a broad front as quickly as possible to establish what works and what doesn’t – before the medical lobby steps up its attack on pharmacy practice.

Click here to download the English version: “Developing pharmacy practice – A focus on patient care”

Good Pharmacy Practice has been inhibited by pharmacy leadership groups and conflict of interest remains the main reason for the deep divisions within the profession.

The PGA in particular has been a compromised organisation for many years and many pharmacy owners would agree that the negotiating results from the last three CPA agreements have not been favourable to the bottom line of community pharmacies.

PSA have taken a considerable amount of time to establish a program favourable to pharmacy practice such as “Health Destination Pharmacy” but they appear vulnerable in areas of their custodianship of codes of conduct and practice guidelines etc.

As previously pointed to, their involvement with homeopathy was none of their business and they have since indirectly been associated with restrictions on other complementary medicine modalities.

This is not a valid PSA function and is simply a knee-jerk reaction to medical lobbyist groups.

While medical practice settings are a valid setting for clinical pharmacists, emphasis needs to be made to ensure that it is a valid alliance partnership and not subject to a set of rules to be imposed by doctors that form part of another agenda.

i2P is interested in seeing paid clinical pharmacy practice services proliferate through community pharmacies, GP practices and a range of other suitable clinical spaces.

Here, the PGA has to undergo a major cultural change, which is not happening appropriately, because they can only think in “top down” models.

An alliance partnership with clinical service pharmacists is required.

That will only happen if individual pharmacy proprietors look to develop partnerships of this type before lobbyists get in on the act – a “bottom up” process.

The culture of allowing medical lobbyists interfere with pharmacy practice is a long established part of pharmacy culture.

While there is some evidence that pharmacy leaders are opposing these embedded processes, more needs to be done – and more energetically than has previously been the case.

The reality is that Pharmacy Practice is a constant for all pharmacists and is not the exclusive province of community pharmacy owners.

The PGA has successfully argued (but with flawed logic) that they should “own” all of pharmacy practice delivered in a community setting, and so have created divisions that now have to be repaired.

Nobody argues that community pharmacy is the major “face” of pharmacy and has been given privileges because of the special nature of this model.

Recognition has to be made that the community model needs a change from the dispensing-centric presentation to a more rounded version that promotes clinical services – a product that pharmacy consumers have requested more of.

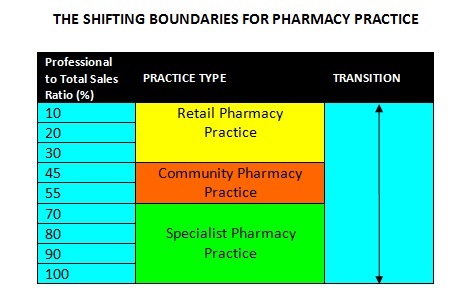

The table below illustrates pharmacy practice (professional goods and services) diluted with different levels of commercial activity.

This table is applicable to any pharmacy community model from any time period.

This simple table illustrates a number of characteristics:

This simple table illustrates a number of characteristics:

* All pharmacy practice involves a percentage of retail sales.

* The higher the percentage of retail sales the more patients are treated as customers.

* The higher the professional content the more consumers are treated as patients.

* The higher the commercial content of pharmacy practice, the larger the practice area.

* The higher the professional content the less floor space is required.

* The optimum ratio for professional sales for a community pharmacy sits in the 45-55 percent area.

* Professional services practices above 60 percent of professional content are more mobile and can be set up in other specialist forms of pharmacy practice e.g. a diabetic clinic can be formed up in a modular office format that can be packed up and then set up in a retail pharmacy (discount or warehouse pharmacy) or a community pharmacy.

The point to reconcile is that clinical services need totally different presentations and training from a dispensing pharmacy.

That also means capital investment, equipment needs, staff and their training, marketing costs and other overheads have to be the responsibility of the clinical pharmacist.

The alliance with a community pharmacy has to be through leasing floor space, or preferably an income-sharing agreement that may include a provision for sharing staff as well.

A common advisory board to both practice companies (community pharmacy and clinical services) would then complete the new paradigm pharmacy.

This is a bottom-up arrangement where risk is shared in the development and marketing of all new professional services.

It also removes conflict of interest problems in pharmacists wishing to prescribe.

Limiting an approval to prescribe to clinical pharmacists and ensuring that no pecuniary interest exists between the pharmacy practice company and the clinical service company, creates a pathway to move forward into a number of specialist services that would have an immediate impact on public health costs e.g renewal of patient prescriptions under PBS rules.

This is the survival pharmacy model that can absorb excess graduates, provide a succession pathway for a senior pharmacist who can sit down (and work productively), and can absorb as many clinical pharmacists (or other health practitioners) in non-competitive specialties that can be delivered from under the same roof (a type of health precinct).

All it requires is a bit of creativity and innovation.

i2P was part of a pilot study in 1978 that proved this concept could work.